The S&P 500 closed at an all-time high last Friday. The new high does not come with the euphoria we saw in January. For example, the Investor’s Intelligence survey is reporting a 3:1 bull-bear spread, far short of the 5:1 bull-bear spread in January. The AAII sentiment survey is now indicating investor optimism, not euphoria. The toned down sentiment and expectations show January’s giddiness has not returned. This is a good sign for the markets.

Trick question: How many stocks are there in the Wilshire 5,000 stock index? The answer is only 3,500, down from a peak of nearly 7,500 in 1997 and roughly 5,000 at the benchmark’s inception in 1974. The supply of U.S. publicly traded shares is clearly shrinking in spite of a growing economy and a surge in the number of new technology (new economy) stocks. But why just half the number compared to 20 years ago?

First, share repurchases by companies are at all-time highs. Often referred to as ‘financial engineering,’ critics grumble as if share repurchasing is a form of cheating. Actually, shareholders who take advantage of buybacks usually reinvest the money in other stocks. The money may be reinvested in companies that need more capital or companies that use capital to grow more efficiently.

CEOs and CFOs know the power of the relationship between share repurchases and earnings growth. For example, Apple has shrunk outstanding shares by almost 25% over the last five years while net profits grew by 7% per year. The combination allowed earnings per share to grow by a compounded 12.9% per year. This certainly helped attract shareholders to their stock.

Second, the sharp falloff in initial public offerings (IPOs) compared to the ‘80s and ‘90s means new issues aren’t replacing stocks leaving the universe. In the U.S., 2014 was the best year for IPOs in over a decade, but volumes in recent years have weakened according to Dealogic. Many companies (even large ones like Uber) prefer to stay private to avoid the pressure of producing quarterly earnings in line with Wall Street expectations, as well as the onerous demands of corporate governance (Sarbanes-Oxley). Some public companies would rather go back to being private to avoid public sector scrutiny. Elon Musk recently tweeted his interest in taking Tesla private, although he walked back that comment this past weekend.

Third, mergers and acquisitions also decrease the supply of stocks, which often serves to concentrate economic power in certain industries. For example, just five banks control almost half of the assets in America’s financial system. Over the past decade, the six largest airlines have consolidated into three, and four companies control 98% of the wireless market.

The law of supply and demand speaks loudly here. Over time there will be more money available for equity investing due to a growing number of investors along with more funds available from the growth of the economy. If the supply of stocks continues to decline as we expect, the supply/demand balance should exert upward pressure on stock prices. And some of the $1 trillion in cash in private equity firms will find its way to the public markets, too. The effect is hard to quantify, but the direction is clear.

So root for more mergers, more acquisitions, more share buybacks, and more companies going private (goodbye Tesla?). Lower supply should increase your returns and put more money in your portfolio.

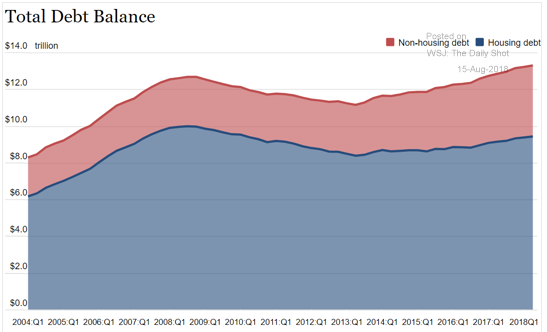

Household Debt Accumulation Continues

While the household debt to GDP ratio remains well below the 2009 high of 87% (65% at the end of Q2, 2018), household debt accumulation is at a new high of $13.3 trillion (see chart). High debt levels and leverage make debtors more vulnerable to rising rates, changes in bank lending standards, diminished liquidity and a slowing economy. Asset price shocks and balance sheet recessions (indebtedness that slows spending) often follow. The 2007 housing crash and prolonged, sluggish recovery resulted from overzealous borrowing.

The Federal Reserve is committed to two more rate hikes this year, and at least as many next, in an attempt to “normalize” short-term interest rates (currently near 2%) to levels commensurate with inflation nearing 3%. While President Trump has tweeted his disdain for higher rates, and the resulting stronger dollar, the Fed seems steadfast.

As we discussed in last month’s commentary, low quality U.S. corporate debt (referred to as risk assets) now represents two-thirds of all outstanding. Government debt accumulation continues unabated (especially at the federal level where annual deficits could soon reach one trillion annually). Borrowing from future generations has become the answer to all problems.

Unfortunately, rising interest rates will eventually pressure those with excessive debt, especially the credit challenged, including households, corporations, and governments to slow spending, forgoing consumption and thereby diminishing growth. The world, especially the developed world, is now awash in debt increasing the likelihood of another balance sheet recession. Excessive borrowing may be the curse of our time though few currently appreciate the gravity of the potential consequences.